Two men dominate the storyline of The Scourge of the Kaiserbird. One was Ernst Luchtenstein, the young German Jewish immigrant and the other Cornelius Fredericks, the Nama, leader of the !Aman of Bethanien, son of Josef Fredericks the second.

The story I tell is fiction based upon facts. Ernst and Cornelius were real people. I told the story of Ernst in Day 8 of this blog. Today I want to focus on the true story of the real Cornelius Fredericks. Because of the paucity of documents I had to do my own research and use my imagination to devise a story, but I knew that I wanted to remain as close as possible to the truth.

Cornelius’s father Josef sold a large piece of land to Adolph Lüderitz in 1883. In the process Lüderitz was guilty of using a term that the Nama people didn’t know – the geographical mile. Lüderitz was well aware that they didn’t know this term and he deliberately kept that secret. There is documentary proof for this in the Namibian archives. In the story I describe Cornelius as an eye witness to the signing, but I have no proof for this. What is beyond any doubt is that this transaction opened the floodgates of German colonists to populate the south of the country. Without this transaction the history of the country may have been quite different.

My first reference to the contact between the two central characters came from the late Dicky Strauss from Kirriis Wes, near Keetmanshoop. He told me of the incident where the new immigrant family, the Luchtensteins, had been apprehended by some or other Nama group with a famous leader. At the time he thought it might have been Simon Koper.

I studied the Nama war in depth and by a process of elimination I determined that it could not have been either Simon Koper, Hendrik Witbooi, Jakob Morenga or Abraham Morris. I came upon a book, The Lonely Grave in the Fish River Canyon, which told the story of the young German soldier that is buried in the canyon, lieutenant Thilo von Trotha. It also tells how the lieutenant came to the country to fight the Hereros in the war that lasted from January to October 1904 and how some Nama scouts loyal to Hendrik Witbooi worked with Thilo von Trotha. One of them was none other than Cornelius Fredericks. They became friends during this terrible campaign which saw the majority of the Herero people being killed.

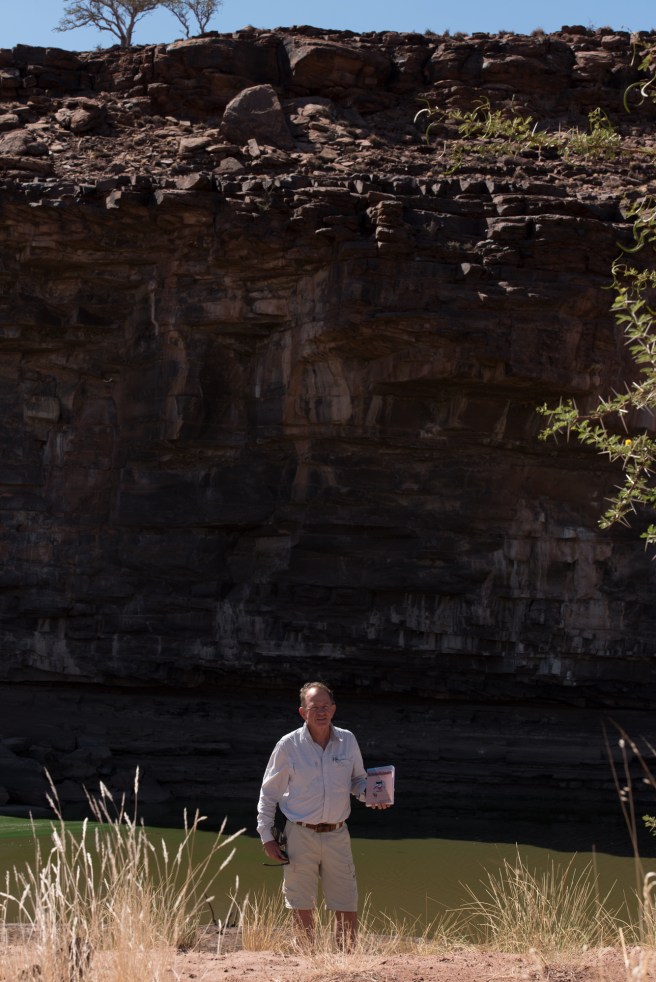

In an ironic twist the same Hendrik Witbooi declared war on the Germans on 3 October 1904. From that moment Fredericks and his erstwhile comrade and friend, Thilo von Trotha became enemies. Despite this von Trotha tried to get Fredericks to surrender and followed him into the vast wilderness of the Fish River Canyon, where he, von Trotha met his fate. The book, The Lonely Grave in the Fish River Canyon, describes in detail how the incident happened and makes it quite clear that Fredericks was not guilty of betraying and killing his friend, but one can forgive the German Schutztruppe who at the time did not have this information, for casting Cornelius Fredericks as suspect Number One. What eventually happened to Fredericks and so many other of his countrymen is however unforgivable.

Some time after the incident in the Fish River Canyon Cornelius Fredericks was caught and imprisoned on Shark Island in Lüderitzbucht, today’s Lüderitz. Dicky Strauss told me of the famous leader of the Namas who were caught after the incident when the Luchtenstein family had been overwhelmed by the band of Namas in the desert. Dicky said that the leader was eventually hanged, but I travelled to Windhoek especially to meet and talk to one of the Fredericks descendants, pastor Isak Fredericks. Pastor Fredericks told me in no uncertain terms that Cornelius Fredericks had been poisoned on Shark Island during his incarceration there. His skull was one of the many sent to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin, where it is still to this day.

The Nama leader of Dicky Strauss’s story and Cornelius Fredericks who fought with Thilo von Trotha was one and the same person. Many years later Ernst Luchtenstein himself wrote of the incident where his mother knelt in front of the Nama leader and begged for mercy. Ernst witnessed how the Nama leader took his mother’s hand and told her to kneel only to God. The Nama leader said that they did not fight women and children.

Once I made the connection between the Nama leader of Dicky’s story and Cornelius Fredericks, the story wrote itself.

At the time it struck me that he was most probably the last living person who had personally talked with a survivor of the war. Captain Fredericks was one of the two nominated people who are engaged in a 30 billion dollar law suit in the USA against Germany for reparation for war crimes.

At the time it struck me that he was most probably the last living person who had personally talked with a survivor of the war. Captain Fredericks was one of the two nominated people who are engaged in a 30 billion dollar law suit in the USA against Germany for reparation for war crimes.

dawned. I take pride today in announcing “The Scourge of the Kaiserbird,” my historical novel set in colonial German Southwest Africa, today Namibia.

dawned. I take pride today in announcing “The Scourge of the Kaiserbird,” my historical novel set in colonial German Southwest Africa, today Namibia.